For Dr. Kaitlyn Gaynor (she/her), Assistant Professor in UBC’s Departments of Botany and Zoology, being able to do research was a key moment of transition in her journey to becoming a scientist.

“I had spent so much time in school reading other peoples’ work. When I began exploring research opportunities in undergrad, I realized that I could be the person that was creating knowledge and writing papers, as opposed to just being a consumer. It was really empowering,” said Gaynor.

Learning that, we got curious about what came before and after Gaynor’s pivotal insight. How did Gaynor get involved in research in the first place? How did her early research experiences lead her to her current interests in the effects of human disturbance on wildlife and to working with us at UBC Botany?

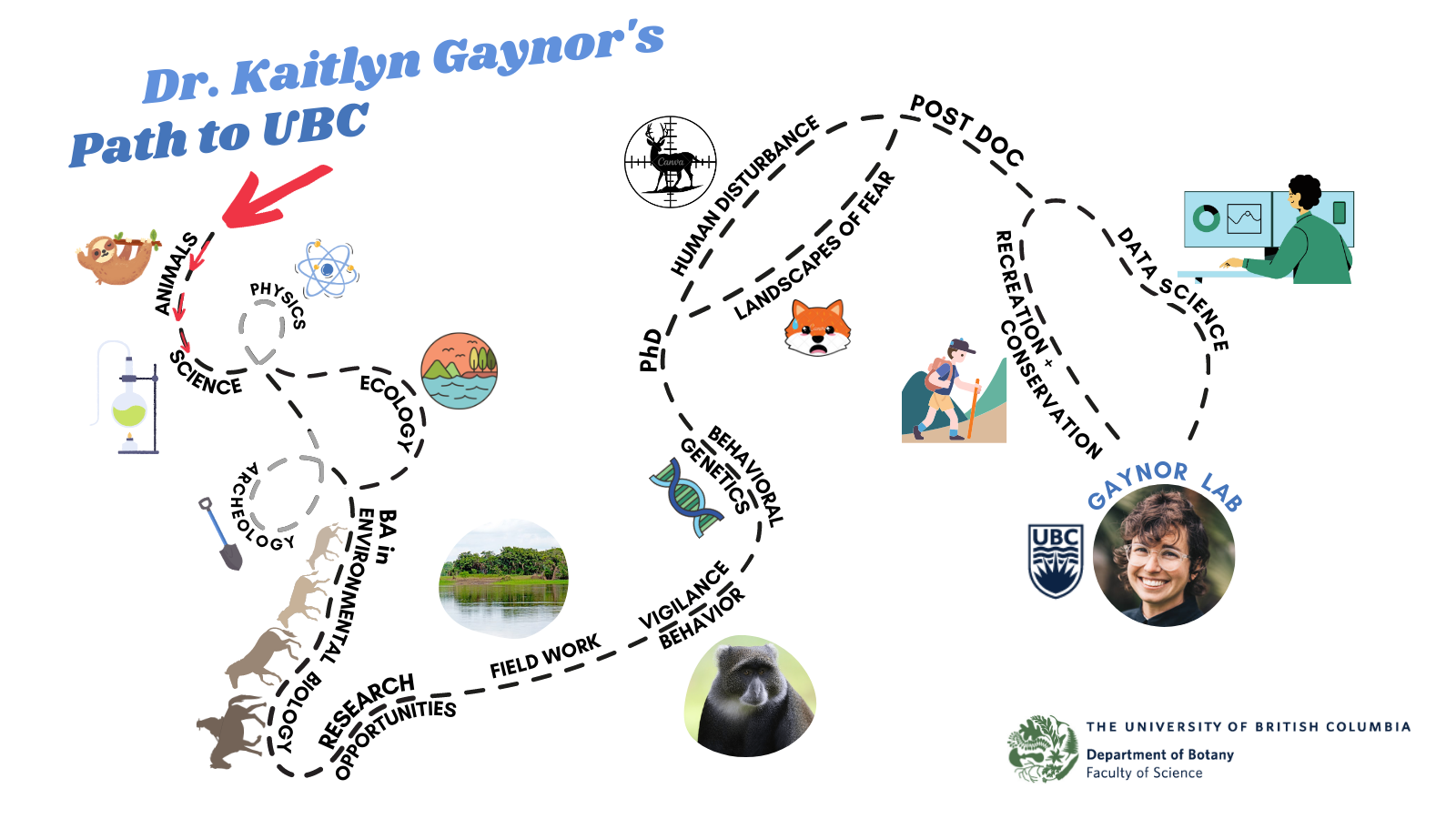

On behalf of young scientists, we asked Gaynor to help demystify her path as a way of offering advice to those who are new to research. The answers are summarized in the graphic above — but the insights don’t stop there. Read on to learn more!

At the beginning of undergrad, Dr. Gaynor didn’t know much beyond the fact that she wanted to do something in the sciences.

She felt a bit “like a kid in a candy shop” with the amount of options for classes that were available and decided to enroll in whatever she could that seemed interesting. This included classes in psychology, archaeology and ecology, and she even considered being a physics major.

Ultimately, one course adjacent to the field of ecology really caught Gaynor’s attention. The class, taught by Dr. Jill Shapiro, examined the history of the human species within ecosystems using the lens of human evolution. Taking into account the fact that she had always loved animals and nature, Gaynor made the decision to major in the department out of which the class was taught: Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology.

“Another deciding factor,” said Gaynor, “was that I felt welcomed, supported and like I belonged in the tight-knit Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology department. I actually came close to being a physics major in my first year, but I didn’t like the large class sizes, the competitive environment, and the hyper masculine culture of the field.”

Exploration remained key to Gaynor’s process.

She continued taking more classes that were slightly outside the zone of her knowledge — such as primatology — leading to her second major in biological anthropology. She also started testing out research opportunities by volunteering in a primate cognition lab, and studying abroad to do archaeology in Ecuador and field biology in Brazil. From these experiences, Gaynor realized that she was really drawn to fieldwork, leading her to travel to Kenya to complete her undergraduate thesis on vigilance behavior in blue monkeys under the supervision of Dr. Marina Cords.

Her undergraduate thesis research was Gaynor’s first taste of independent research: a project that she had designed and executed from start to finish. She was hooked. “I knew that was it. That's what I wanted to do,” she said.

“After I graduated I went back to that field site in Western Kenya, worked for the professor who was my advisor in undergrad, and managed the research project for a year.”

Gaynor began thinking about graduate school. But before she applied, she wanted more experience as a researcher. She decided to broaden her skill set by working in Dr. Dustin Rubenstein’s lab investigating behavioral ecology (kin selection and social behavior) and genetics in snapping shrimp and starlings.

Her years as a researcher hugely informed Gaynor’s PhD project. While in Kenya, she observed monkeys feeding in trash pits, living in fragmented plantations, and eating the mud from the exterior of houses. In other words, these monkeys were living in anthropogenic contexts that were different from the context in which they had evolved.

“For my PhD, I decided to bring together my interest in animal behavior with my questions about the growing role of humans in the environment, ultimately hoping I could positively influence conservation outcomes,” said Gaynor.

Through continued fieldwork, Gaynor investigated the effects of human disturbance, especially hunting, on wildlife in Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park. She observed that in some ecosystems, a “landscape of fear” emerged, in which animals respond to human disturbances by changing their behavior by, for example, becoming more nocturnal.

The research had informative results for conservation efforts, so Gaynor was motivated to remain in the same discipline and contribute further knowledge. For her postdoc, she wanted to bolster her data science skills after years of building up expertise in fieldwork, which led her to a three-year residence as a fellow at an environmental data synthesis center.

At UBC Gaynor will use her insights from across systems — from the study of animal behavior, field ecology and data science — to positively influence biodiversity and conservation.

We concluded by asking Gaynor a few more questions.

What tips would you give to students looking for research opportunities?

Answer: I got my first research position working in a primate cognition lab by cold-emailing the professor leading that lab. It was really scary! I understand the fear of reaching out to a professor and the vulnerability required to introduce yourself in an email, but ultimately I think you shouldn’t get discouraged. If one opportunity doesn’t work out, something else will.

Opportunities are not always going to be advertised far and wide, which is a real problem from an equity standpoint. But what this means for you, as a student, is that you often have to ask your professors and advisers about what opportunities are available. Ask, and then be open to saying yes even if an opportunity isn’t exactly what you had envisioned.

I was open to a lot of experiences that weren't part of any set plan but which I ultimately found really formative. My first experience with fieldwork came about after I saw a poster advertising a summer program in Brazil that involved research, which I applied and got into. I happened to mention to my academic advisor that I would be going to Brazil for a month out of my summer and that I didn’t know how to spend the rest of my break. My advisor informed me about a course he’d be teaching in Ecuador for the month after, and he encouraged me to apply and join his team as a volunteer, which I did. These international experiences were life-changing, and I wouldn’t have found them if I hadn’t kept my eyes open and asked questions.

Is there a benefit of taking classes outside of your main area of interest? Did you have difficult experiences taking classes you didn’t like?

Answer: There were definitely some classes that I was required to take that I was not enthused about. But, taking classes is all about exploring and defining your interests. You might be surprised like I was. I remember having to take a course in earth and atmospheric sciences, which didn’t seem to apply to my interests as an ecologist, but it ended up being one of my favorite classes because it increased my literacy around climate change, which is of course very relevant to modern ecology.

Not all my classes turned out to be interesting, though. There were aspects of my journey that were hard. There were aspects that were not fun. There were classes that I took that I really didn't like. In those difficult moments, it can be hard not to take it all as a sign that you should quit.

But struggling in the learning and practice of science does not necessarily mean that it’s not right for you. Sometimes it can be a question of the learning environment. I’m trying to create more inclusive spaces where students can see themselves and feel welcome, and I encourage students to seek those spaces before leaving science.

What is a commonly held belief about science that you want to dispel?

Answer: Science does not necessarily have to happen in controlled settings, i.e. in the lab with microscopes and pipettes. The laboratory is a great way to do science for a lot of people. My method is with my hiking boots on, a pair of binoculars in hand, and a clipboard. Science is about coming up with an idea and finding a way to test it, and this can include other ways of knowing that are currently outside our traditional Western scientific framework.

Finally, I always like to share messages of hope around biodiversity. We are in a giant environmental crisis, but we don’t often get to hear about the successes of conservation efforts. There are a huge amount of people that are dedicating much of their time and energy towards restoring landscapes. And I know that there are students who are waiting to apply their different skills to make things better. I hope I can encourage and help those students.

We’re excited about the opportunity to collaborate with Gaynor’s research program. You can find more information about her ongoing work by checking out:

- Gaynor’s website and her Twitter profile,

- Video interview with Gaynor on Finding Solutions for Coexistence,

- Q&A by Zoology,

- Gaynor’s reflections on how her identity intersects with her fieldwork,

- A course she is teaching in 2023, BIOL 300: Fundamentals of Biostatistics,

- and check here for opportunities to join Gaynor’s lab!